Hello all and welcome to the blog on reloading:

I got into reloading back in 2010 as a hobby. I was a broke college student and was shooting on a weekly basis, so I needed a cheap way to fuel my shooting habit. In those days, you could reload 9mm for 10 cents a round and 5.56 was 20 cents a round. I worked at a gun shop, and with my discount, I could reload for even cheaper.

I had a studio apartment and set up a reloading bench in the kitchen. The initial cost for me was $350 and I still have the original RCBS Rock Chuker Supreme press. While other parts have worn out with use, I still have the original press, charge thrower, scale, and book that came with the kit.

Sadly, the days of cheap reloading are over. Components are three times what they used to be. A box of primers that was $30 now costs between $100 and $120.

I am still reloading, but the purpose has shifted. I buy store ammunition for training and practice, but I reload for precision. For that specific purpose, it is still an extremely valuable skill. Reloading your own rounds means you can make micro-adjustments to the ammunition that is specific to your firearm. The other cool part is you can load “exotic” rounds for long range, meaning using heavier weight projectiles you can’t buy in stores. If you plan on getting into long range or precision shooting, I highly recommend taking a closer look at reloading.

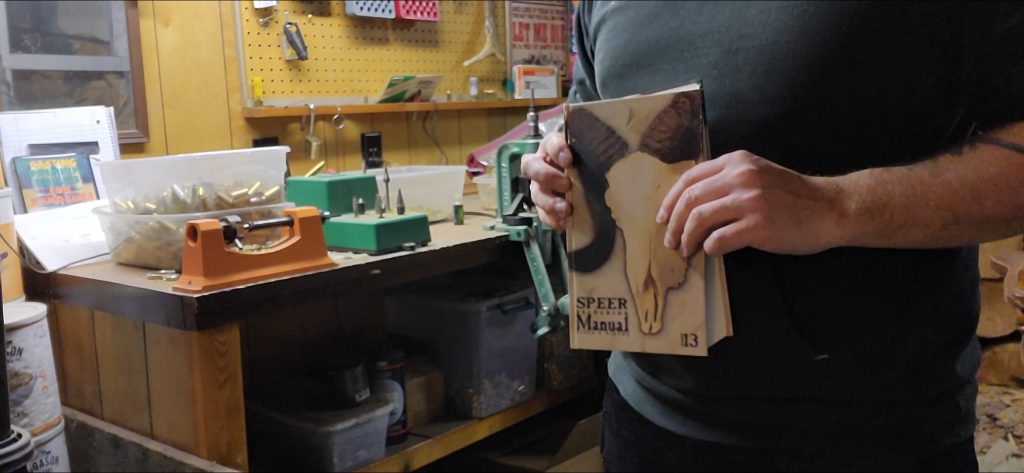

If you plan to reload, the first step is to READ THE MANUAL!!! This lays everything out, from safety tips to recipes, to what different powders do. This is a wealth of knowledge and must not be discarded. If you want to turn your firearm into a dangerous explosive, and maybe lose a few body parts in the process, go ahead and disregard the manual, and use the wrong powder as well. If you want to do it right, read the manual! Every manufacturer of projectiles has its own reloading manual, and you can get data for powders online as well.

The second step is to find the ammunition casings, or brass. This is the easiest and cheapest part of the process. Go to your local range and scavenge for the brass of the caliber you shoot. Discard the discolored brass, or the brass with corrosion. Steel and aluminum casings need to be discarded and not used. Steel can damage your dies, and aluminum is only meant to be fired once. You also want to look for Boxer Primed casings (ONE large hole in the center of the base). Berdan Primed has TWO small holes at the base of the casing and will destroy your de-priming die.

After the initial visual inspection, you need to clean the casings. I have a vibratory cleaner that uses crushed corn cobs and walnut shells. There are also sonic cleaners and tumblers with small stainless-steel rods. These work very well and typically clean not only the inside, but also the primer pocket of the case. These are expensive, however, and since they use water, you have to dry the brass quickly before corrosion sets in. I have never upgraded because my cleaner works well enough for me. As you are putting the brass in your cleaner, be sure to look for splits, small cracks, or other anomalies. This is the second visual inspection I do on my brass. After the brass is clean, I inspect it again. Usually, the small cracks become more apparent when clean.

The next step is to remove the old primer. Depending on the die set you have, two things need to be kept in mind: 1) most dies require some form of lubrication such as an approved oil or spray to keep the case from getting stuck inside the die (You will only forget to lube the case up once, as trying to get it back out will result in a level of frustration I cannot adequately describe), and 2) most dies size at the same time, this means opening the neck up so you can put the next projectile in it. Reloading is done a lot by feel, and it is difficult for me to describe what a properly sized and de-primed casing should feel like when it is done correctly. But it should be smooth, then a small amount of pressure, then a “thunk.” The primer will fall out and you need to visually inspect the cartridge again. If you have the die set incorrectly, one of two things will happen – the throat of the case will be too small (not set deep enough) or the case neck will be smashed down and you will see creases (set too deep). Time for another visual inspection.

The next few steps can be done at the same time. Look in the manual, and you will see a minimum case length and a maximum case length. I trim all my brass to a minimum with a case trimmer. It looks like the front of a water pump to your car. A shaft with blades on the end. You put the brass in the cradle and use a drill to trim the neck. The great part is it has set screws so you can measure once and set it. Every few rounds, however, I use my calipers to verify they are all the same size, along with another visual inspection.

Next, I swage out the flash hole. Sometimes cases come from the factory with burrs in the hole where the primer flash is directed to the powder. If you want a consistent burn, and reliable ignition, this needs to be done. Then I clean out the primer pocket. When fired, residue from the primer gets all over the primer pocket of the case, just like creosote in a chimney. I use a wire brush on my case prep machine to get rid of it. This is so the primer is set in the primer pocket uniformly every time. The de-burring tool looks like a drill bit with only one groove at the tip. There is a bell on the end with a set screw, again so you can do multiple without readjusting. It is super simple to verify it is working correctly – if it is set correctly you will feel a bit of resistance when the burr is removed. If you feel too much pressure, or none at all, it is not set correctly. Followed this with yet another visual inspection.

Then I de-burr the case neck. After being trimmed there will be an excess of brass on the tip of the neck. This looks like a jagged ring, and it needs to be removed. When de-burring the case neck, it is normal to see flakes of brass falling off the case. When you are finished, there will be a small ring of shine at the case mouth. Almost like a knife blade, the case neck will be beveled just a little bit. This aids in seating the projectile. I usually put the cases back into the cleaner to knock off any excess brass pieces I missed. This is just something I do and not mandatory. Perform another visual inspection.

Next comes priming. Just like the difference in pistol and rifle powders, there are different primers for pistols and rifles. There are also sub-sections of rifle and pistol primers. They include small rifle, magnum rifle, bench rest rifle (match grade), and large rifle. This is the exact same for pistol. I can go into the differences between each one but for brevity I won’t. What you need to remember is, make sure the size is correct, different cases only accept certain size primer. (Example the 5.56 will only take a small rifle size primer, and a .357 will only take a large pistol primer.) The priming tool looks like a tube with a pan on one side and a hand hold on the other. You put the primers in the pan and make sure the forcing cone is facing up, it looks like an X. Then one at a time you put a case on top and squeeze the hand hold. While squeezing it should be a smooth motion and not much resistance. If you feel a large amount of resistance check and make sure the primer has not turned sideways. Also, if pressure is felt, make sure it does not have a “military crimp” If it does, it needs swaged out. NEVER POINT THE CASE YOU ARE PRIMING AT YOUR FACE!!!! Just like firearms, we always keep it pointed in a safe direction. While I have never had it happen to me, I have had colleagues tell me they have set primers off doing this. A primer going off in your face is a great way to end up in the hospital, with a missing eye. Then guess what? Another visual inspection.

Now for pouring powder. This part requires the utmost respect. No drinking alcohol, watching TV, having a conversation, nothing. This is where things can go really wrong really fast. I have seen the aftereffects of a “double load” of pistol powder, he had to buy a new 1911 because his was split in multiple places. This is what I mean when I said turning your “firearm into an explosive.” A double load of pistol powder into a pistol case, or a full load of pistol powder into a rifle case can cause catastrophic damage to you and your firearm. Again, READ THE MANUAL!!!! Do not deviate from the recommended powder load in your particular recipe. If the manual says 45 grains of X powder as a max load, do not put in 46. More velocity does not mean more accurate, and you are risking over pressure. You must make sure you are using the CORRECT powder. I usually triple check this in the recipe book. I learned my lesson by getting distracted and not pouring powder in a couple of .45 ACP rounds. It was a batch of 500! And I did not know which ones had powder and which ones didn’t. That was SO MUCH FUN! I had to pull every round and start over again. Learn from my mistakes. Focus.

When pouring powder, set your cases in a case holder and begin measuring your charge thrower by filling the thrower with the CORRECT powder, then backing the screw out and using your scale to measure. Different scales use different ways to measure weight. Mine has a series of weights with teeth and a marking on the arm and on the pylon that need to be even with each other. You place the weight on the tooth of the correct amount and add powder until the white marks line up. I usually back the screw off the powder measure a half turn at a time. Once the powder is dialed in, I tighten the set screw. Pouring powder goes quickly but I usually weigh a few rounds a batch to make sure it is still correct. Again, when pouring powder, we want to triple check everything. Any guesses what comes next? Yeah, another visual inspection. With this one I use a flashlight and make sure all the powder levels are the same.

Finally, the last part of the process WOOT! Seating the projectile is a wonderful feeling. To start, I seat the projectile very slowly at first, just half a turn of the die at a time. You do not want the projectile to be too deep as this can cause excess chamber pressure, nor do you want it out too far as this can cause the projectile to detach from the case under recoil in the magazine. This is the one part of the process where you have some wiggle room. Your firearm’s throat size determines how far out you can set the projectile. To get the most accuracy, you want the tip to just touch the lands and grooves of the barrel. This stops “chamber gap” which can lead to inaccuracy. This is where the projectile has to move a small distance without any rifling to stabilize it. We are talking about microns of distance, but it does have an effect. Unfortunately for the service rifle folks (me included) the magazine length dictates the maximum COL – Cartridge Overall Length. The COL is found in your reloading book.

After the projectile is seated, you want to check for looseness of the projectile, by that I mean it should not spin freely, or move up and down, and the case neck should not be bowed out. I always make one round without a primer, or powder to make sure it cycles correctly. Destroying one round is way easier to stomach than having to go back and pull multiple projectiles because they don’t fit correctly.

Time for the final visual check. This one will be different. You should feel a sense of pride. You made these from scratch, and these are your freedom seeds.

Remember to store your reloaded ammunition in a cool, dry place. Label the outside with the grain of the projectile, and the powder used. This comes in handy when you are accuracy testing.

When shooting, pay attention to excess chamber pressure. The primer will look bowed out, or completely flat with no divot where the firing pin struck. In extreme instances, the case will split, or the back of the case will expand to the size of the bolt, causing it to stick. This will jam the gun to the point where it needs a gunsmith to be opened. If you see any of these signs, STOP firing the ammo.

If you made it this far, I really appreciate it. Writing this out was tedious, but it’s something I believe every gun owner should know how to do, even if they don’t do it. Multiple game animals over multiple states have been taken with ammunition I made. That fills me with pride every time I start a new batch of ammunition. If you want to know more, please follow our YouTube channel, or reach out to me, I would love to hear from you.